Excerpts from ‘Southwark Monthly Meeting, etc’, a chapter of The London Friends’ Meetings

William Beck and T Frederick Ball's 1869 book The London Friends' Meetings has recently been reproduced in facsimile edition. Here we present some excerpts.

In the same year ‘Susan Atkins has desired Robert Hogell to put away his wife and take her, Ranter-like, and has endeavoured this matter several times, saying it was a revelation from the Lord,’ and persists in her conduct and ‘wont condemn it.’

Thus we see from the foregoing extracts signs of that spirit tending to make the liberty of the truth degenerate into licence and rant, which George Fox, the lover of order, so resolutely encountered and defeated.

Marriages

After a general establishment of meetings for discipline in London, George Fox felt their care was especially needed in the case of marriages, to prevent disorders that had been committed (see Journal), through lawless conduct or misplaced ideas of spiritual guidance leading to neglect of the customary restraints and usages.

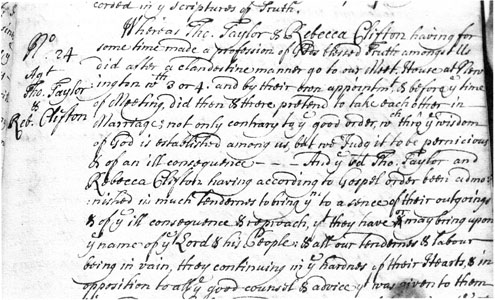

It seems from the old Horslydown minutes that irregular marriages were by no means infrequent. The following are examples: Tenth Month 18th, 1667. – ‘John Farant and Ann his wife was here at this meeting, and was spoke to about the manner of their marriage, and they have declared that they do accept of one another as man and wife, and have declared they intend to and will live lovingly together until their lives end.’

In the following year we find a notice of, ‘Will the Chandler, and the woman that has accompanied as man and wife without due publication,’ who promised satisfaction to the meeting. This probably means some public appearance and declaration.

In 1672 two Friends appear to propose marriage, and are described as ‘pretty tender and submissive.’ Friends order the young woman to take a lodging till the marriage. – ‘She confesses she came to live with him through ignorance.’

In Sixth Month, 1675, ‘two came and acknowledged their sin in living as man and wife, and promised to be faithful to each other.’

The subject of marriage claimed in many ways increasing care and attention on the part of Horslydown Friends. Looking upon themselves as a distinct people, and, in fact, ‘the people of God in scorn called Quakers,’ they were very severe on those who took ‘a man of the world,’ or ‘a woman of the world’ in marriage. Thus we read, in 1667, of three Friends being appointed ‘to go to Thomas Gesope and Thomas Sturgess to lay their wickedness upon them for their taking of wives of the world.’ They would hardly recognise the going before a priest as a true marriage, and ill judging another Friend they speak of him as ‘taking the woman he calls his wife.’ In many cases they obliged those who had been thus married to go and testify against it to the priest who had married them, as well as to Friends and to their neighbours.

Not only did the Monthly Meeting judge those who had married contrary to rule, but took care to give advice beforehand when necessary. In 1670, we read of a Friend having to be visited, ‘to warn him from the woman that sells oranges, as to marriage, for she is a bad woman, and Friends cannot own him if he join himself to such a one.’ This Friend persisted in marriage with the orange-woman and was subsequently ‘denied’ for the same.

The following minute (written in 1672) is a further instance of the care exercised with regard to matrimonial connections: ‘Thomas Blake, Prudence Mags, he lives in Whitt Shaple and she in Southwarke Parke, has propounded their intention of marige and ffriends does find A simplicity in the Man and a tenderness though but lately convinced. Themselves Advised and counseled them to wait to feel that true [word illegible] that first convinced them and as they find that to lead them to proceed in it.’

Deliquency

We find that Horslydown Monthly Meeting in its early days was troubled, not only by those who pleaded or practised an unscriptural liberty, but also by a numerous class who made profession of the Truth, but were very far from evidencing its possession by their daily lives and conversation.

From 1666 to about 1670 numerous are the cases recorded on the books of drunkenness, fraud, gambling in alehouses, beating wives or servants, &c. Thus we read of an appointment to visit ‘old Patin, the smith, about his getting drunk and beating his daughter he used to beat his wife formerly.’ Again, ‘Ralph Yonge, at Horslydown stairs, plays at ninepins and passes bad money.’ Ninepins was evidently a favourite game; one Friend seems to have beguiled the period of his imprisonment with it. One Will Stuart, a little Scotchman, is judged and denied as ‘an habitual cheat.’ In 1670 one woman wants to be assisted in a passage to Jamaica, but the Monthly Meeting informs her that ‘she is so bad’ that they won’t help her. In many cases the misconduct was long continued; in 1668 William Horton brings in a paper ‘condemning his actions for fourteen years past’, so that his misdemeanors must have commenced with the very origin of the Society in Southwark.

And here we may pause to remark that the disciplinary notice extended to these delinquents seldom terminated in the disownment of the individuals. If, by persevering in visits and exhortations, the offender could be got to write and circulate a paper of condemnation he was again received into unity, though of course under watchful oversight. But those who persisted in their ill-doing or refused to repent were ‘denied’ in plain terms. Thus, in 1668, they record that ‘William Styles, once a pretty Friend, has become wholly apostatised and at present lost as to truth.’ Those who were denied, or, as it was afterwards termed, disowned, were considered ‘out of unity,’ or ‘of the world,’ and if they died in this state, their bodies were denied sepulture in Friends’ burial-ground. We find in one case of this kind a turbulent relative threatening ‘to break the door down’ if he couldn’t have a burial-note.

It is a strong evidence of life and power in the Monthly Meeting that its treatment of delinquents did so frequently result in the repentance and reclamation of the offenders. And in a few years, doubtless in part owing to this care exercised by the faithful members, we find the cases referred to above becoming much less frequent. But of course the Conventicle Act and other cruel laws had also a large share in winnowing the chaff from the wheat. As a further illustration of what the Monthly Meeting when first established had itself to do in this way, we may mention that the subject of fraud was one of the delinquencies that needed care in early times, and in 1667 we find some Friends brought under notice for using false measures. The Monthly Meeting was very anxious that its members should stand clear before the world as honest traders. In 1670 they order Friends that are coopers to have their casks exactly measured, and if they are not exact they are to write on the casks a statement of such deficiency. Shortly afterwards the Monthly Meeting ordered an exact gallon-gauge to be obtained and kept for purposes of comparison (see below).

Prisoners

The care of such of their members as were in prison was a matter likely to claim attention from a Church whose members were at one period liable to be dragged off in the very act of worship, and afterwards had to hear its treasurer (for instance) report, as he did in 1683, that being under a ‘Ritt of excommunication,’ and expecting daily incarceration, he had sent in his accounts, for a new treasurer to be appointed. Amongst various evidences as to the care of their friends, we find this entry in 1684: ‘Paid Thomas Hudson for canvis to putt Round the Greate Bed where friends lodge, yt are prisoners in ye Compter in tooley’s Strete, and is to remaine there for the service of friends yt are prisoners hereafter.’

Horslydown Monthly Meeting, moreover, did not neglect the counsel of George Fox ‘to requite gaolers when they have showed kindness to Friends.’ For this cause two Westphalia hams and other matters, to the amount of £1 18s. 10d., were presented to the marshal of the King’s Bench, and on another occasion £2 to Stephen Draper for the same reason.

Thus varied were the subjects needing the exercise of discipline, so as to restrain, correct, and reform disorderly walkers, in the early years of the Monthly Meeting, when the ‘mixed multitude,’ attracted by the fervour of the early preachers, came to be moulded to a life of regular and orderly walk. The extracts are interesting, as Southwark is the only one of the six London Monthly Meetings whose records at the commencement are preserved; they evidence the state of the Society in the period succeeding that activity of missionary effort which marked the time of the early preachers, the loss of whose formerly frequent presence through death or imprisonment soon showed itself in the increase of disorderly walkers. The contact of the early meetings for discipline with these is thus shown us on these Southwark books. By them we can appreciate the cause of that joy so evident in the pages of George Fox when he found Monthly Meetings well established.

You need to login to read subscriber-only content and/or comment on articles.